In the 1970s, a group of Washington citizens concerned about the influence of money in politics determined to do something about it.

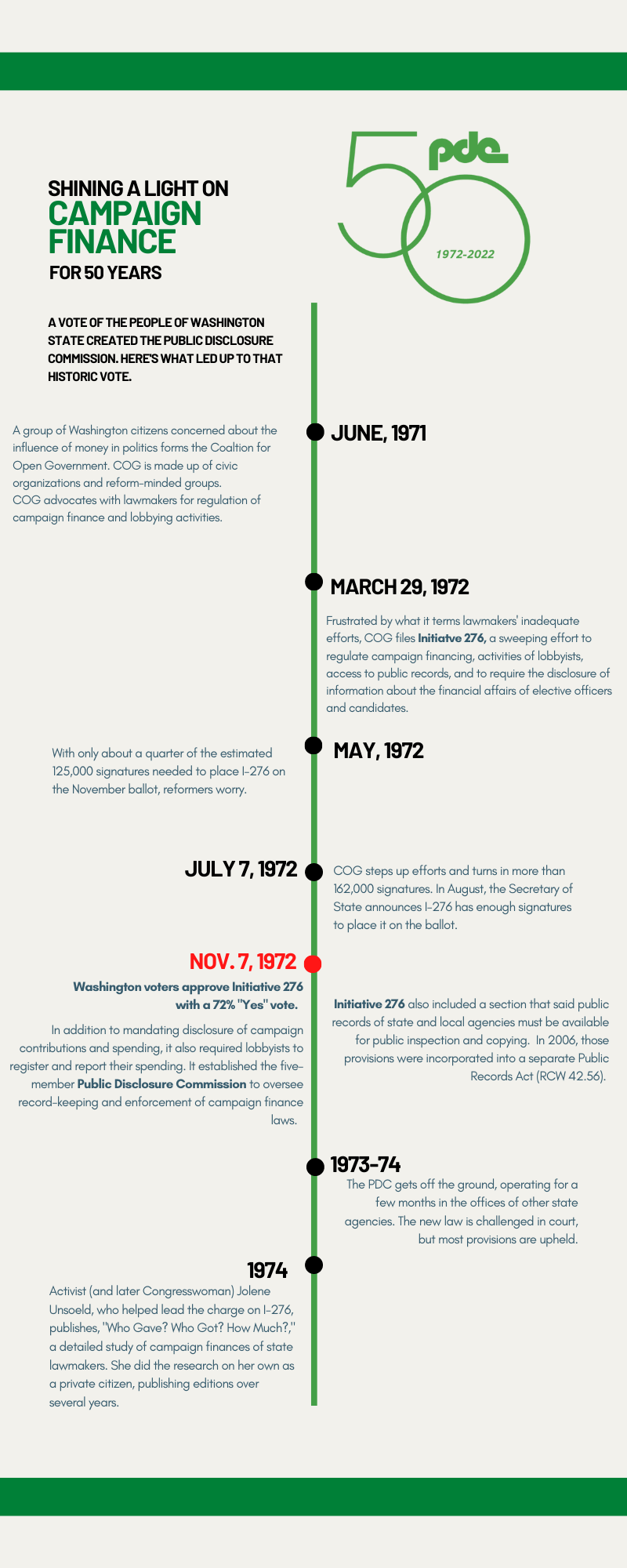

They formed the Coalition for Open Government (COG) in June 1971.

COG included representatives of the League of Women Voters of Washington, the American Association of University Women, the Young Lawyers section of the Seattle-King County Bar Association, the Municipal League of Seattle-King County, the Seattle Press Club, the Washington Environmental Council, the Washington Council of Churches, CHECC (a Seattle group formed to support municipal candidates) and Common Cause.

The Legislature passed the Open Public Meetings Act in 1971, but could not agree on a path forward to increase transparency in the areas of campaign finance or lobbying.

When lawmakers reconvened in January 1972, a bill to regulate both areas, drafted by COG, was waiting for them. Gov. Dan Evans favored reform, but legislators bypassed the COG bill in favor of bills of their own making along with a pair of referenda attached to them.

COG decided the only way forward was to file an initiative to the people on March 29, 1972. Members worried that their proposal, Initiative 276, would be overshadowed by not only the legislative referenda but a slew of other ballot measures, including one to allow greyhound racing and another to privatize liquor sales.

By May 1972, COG had gathered only about 30,000 of the more than 100,000 signatures needed by July 7 to place I-276 on the November 7 ballot.

An intense campaign by I-276 supporters, fueled by endorsements, constant media coverage and hard work, put the campaign over the top in time, with more than 160,000 signatures.

The total cost of the campaign: just $13,000 – more than $90,000 in today’s (2022) dollars. Compare that to the more than $11 million spent in support of the 2014 campaign to establish charter schools in Washington.

COG’s efforts were a success. On election day, Nov. 7, more than 900,000 Washingtonians – 72% of those who voted – agreed to establish one of the most comprehensive campaign finance regulation systems in the country.

It required disclosure of the sources of campaign contributions along with disclosure of how the money was spent , mandated reporting of personal financial affairs by candidates as well as elected and certain appointed officials, and regulated lobbying activities. It established the five-member Public Disclosure Commission (PDC) to oversee this activity.

The initiative laid out a series of 11 statements of policy, which were codified into law. (RCW 42.17A). One of those statements summed up the thinking behind the initiative: “Our representative form of government is founded on a belief that those entrusted with the offices of government have nothing to fear from full public disclosure of their financial and business holdings, provided those officials deal honestly and fairly with the people.”

From the outset, the PDC embraced that philosophy. It continues to do so a half-century after voters approved I-276 and will continue empowering the public to follow the money in politics.

(Much of the material for this article comes from “The People’s Right to Know,” by Hugh A. Bone and Cindy M. Fey; 1978)